Lost Omens: The Mwangi Expanse (An Informal Review)

stop asking me to bless the rains, it's not gonna happen

Hey there! Let’s talk about Pathfinder.

For those who know me, it’s not particularly surprising that I am prone to the immense crime of reading lore for things I’m not explicitly ‘into’. When my girlfriend first started playing Pathfinder, I wanted to join in in any way I could without actually being part of a campaign. This manifested as me reading lore for some species and quickly feeling dismayed. More than that, I was puzzled. What I was reading was wildly racist, though still in the realm of fantasy racism. And yet, my girlfriend hadn’t said anything! Despite playing a goblin, despite her noted love for monsters, she seemingly had no objections to what I was looking over! What gives?!?

… Turns out I was reading 1e.

Like its estranged parent DND, Pathfinder has a long history. It was first released in 2009, and as you might guess from its origins as a DND offshoot/competitor/reimagining, it was incredibly bigoted. Looking over old Dungeons and Dragons books evokes the same sense of horror in me that I felt while reading older Pathfinder materials. Oriental Adventures alone makes me want to hurl, and it’s hardly the sole example of racist DND stuff from the 80s.

2009, naturally, was not much of a better time in terms of avoiding orientalism, fetishization, and exotification of marginalized cultures. I should know, I remember it (vaguely). Growing up Black is, uh, an experience. Let’s say that. Both WOTC and Paizo have pledged to work against old racist narratives involving groups like Black people (hi), Romani people, and so forth. If they’ve succeeded will be a continual question if I continue doing these reviews. In some ways, mostly where Wizards of the Coast is concerned, I’d say no. But Paizo has done a lot on their end that I can say ‘Yeah, this is a start!’

Pathfinder Lost Omens: The Mwangi Expanse is not only an attempt to redo this region based on Africa to be more culturally sensitive. A heap of Black authors have been involved in every step of the creation process, working on everything from various ethnic groups within the region to reworking gods to fit African diasporic folklore and more. It’s cool shit! And since it’s cool shit, I want to do what I do on this Substack and discuss it all with you in an informal manner.

Now, the book is set up with sections. This is a very big book though, so I’m not going to cover every single section. That would be agony to write and read. But I want to discuss what I like, what surprised me, and what I think I would do if I was playing a campaign set here. Cool? Cool.

Let’s do it.

“Super Fleshed-Out History” for $1,000, Please

To start with, I am not going to review all of the history section because lord. It is a lot. There is a giant-ass timeline strewn across multiple pages, it throws in terms I never heard of before touching the book, and it’s very clearly written for true history buffs for this world.

Honestly though, I don’t think that’s a bad thing?

Here’s the thing about worldbuilding fans. We’re often stereotyped as utterly identical. We must all be interested in every aspect, right? From food to culture to history, that’s how we’re seen. But that’s simply not true. A lot of people tend to lean towards their own little subset of interests. For me, I’m always compelled by various cultures. Call it the latent cultural anthropologist in me, but I like seeing fictional religious factions, different nations, and how the people within them react to the societies around them. I do not give a shit about history beyond how it can help me contextualize why different nations exist and interact in specific ways.

Worldbuilding isn’t just for me though. It’s for everyone! It’s for the people who like making recipes based on fictional dishes. It’s for the people who painstakingly discuss how clothing styles would actually work in a made-up country. It’s also for the people who like 12 pages of historical word vomit and memorize timelines like I memorize Pokémon names.

That being said though, while I don’t think it’s bad, I will say the most interesting history bits are legit repeated in other sections of the book, soooooo… Sorry to the serpentfolk or whatever, but maybe you need to get good and be more compelling. Consider that for a moment.

Woah, That’s a Lot of People!

Speaking of history and where it’s repeated, we need to discuss Afro fantasy and the elephant in the room: slavery.

The other day, while idly seeing how Tumblr talks about this area (big mistake), I saw someone call this ‘fantasy Wakanda’. I do find it to be offensive, in the way that the smell of manure offends the nose, that Certain People (one might even say crackers) can legitimately only conceptualize fictionalized African-based settings in terms of Wakanda. Wakanda is a very specific nation that fulfills a particular fantasy for Black people. Wakanda is meant to represent the idea of a highly advanced African nation, complete with technological advancements that outstrip Europe’s idea of ‘progress’, that retains pre-colonial cultural elements unshaped by European forces. It is not only the dream of an uncolonized African nation, but it is a direct response to the idea that Africans are primitive, incapable of understanding technology, and have nothing to offer in terms of spiritual and scientific knowledge. (This, of course, does not erase the fact that it was invented by white people and is often critiqued by other writers in terms of how it is presented in comics and movies.)

Similarly, a common trope in Afro fantasy across the diaspora is the idea of uncolonized land where we hold true power, where our languages are respected and our autonomy is unquestioned. The Mwangi Expanse in general is an area mostly unaffected by colonial forces. And yet, there are white people. Why? Slavery. Colonialism. The scope of it is smaller, but it is still highly present. It’s impossible to discuss the Sargavans without mentioning that, yes, slavery exists in this work. The Bekyar, to me, represent those within the continent who would sell other Africans to colonial forces for profit. Their avoidance of abolitionist movements and disregard of ethical critiques of their practices also hammers this home, even if their association with demons and devils is a little… not subtle?

Beyond that though, I’m also glad the elves, dwarves, and halflings in this region are also Black.

It would have been easy to simply have some Black humans and ignore the human-like designs of these other ancestries. Plenty of series do if they remember Black people exist at all. There’s this sort of idea that having a Black elf would be unrealistic and disruptive. I, of course, think those people should be exiled from society, but it’s not up to me, unfortunately. Still, I find the design work and lore here to be fascinating. Every introduction to a fictional culture should make me want to read a book or see a show about that culture, and this book nailed that.

I especially feel that the sections on how relations occur between different groups across the region makes everything feel more interconnected. These aren’t random peoples living in a vacuum. They are all together in this space, having moments of connection and animosity. They all have different cultural beliefs, ones that even cause schisms from time to time. It’s a neat approach.

Out of the new ancestries and heritages and whatever in this book, I probably like the anadi the most. I enjoy how they’re a neat reference to different depictions of spiders in folklore, allowing for both a giant arachnid form alongside a more humanoid one. But I like the conrasu as well just due to how unique they look!

In general, Pathfinder has a lot of options for people who want to play really unique characters. Yes, they have plenty of humanoids. But you can also play as hyena people and whatever this thing is. It’s cool!

RELIGIONNNNNNNNNN

You know what else is cool? Religion.

It is my firm belief that religion in fantasy settings is at its most interesting when it a: takes inspiration from religions that are not Christianity and b: interestingly grapples with the realities of a world where gods are documented beings that mingle with mortals and who you can actually photograph and such. By now, I have read several books that involve religion in Pathfinder, though this one was the first. As a result, I was impressed both by the differences in terms of how DND religions function versus this and also by the clear inspiration this book takes from African and Afrodiasporic faiths and traditions.

Before I get into the latter point, I want to get on my soapbox for a moment and talk more about the rest. I’d like to think I’ll review some other Pathfinder books one day, but that’s honestly dependent on a lot of different factors that are mostly out of my control. Because of that, I just want my stances to be clear in case I never get to expand on them in another post like this.

For DND, religion is often pretty pathetic. You present a blurb on a god, mainly for the clerics. Then you throw out ‘evil cults’ with ‘evil cultists’ who invariably worship demons and ‘evil gods’ that make no sense. As in, not only is it antithetical to how cults actually operate in terms of execution 90 percent of the time, but the gods in question seem bizarre in terms of having worshippers at all. I always end up going “and why would anyone pray to them in earnest?” which is a bad thing to have kicking around your brain in terms of the faith system you’ve designed.

Here, people usually bring up the Greek pantheon in all of its contradictory nature. “Isn’t Zeus unpleasant too, Nyx?” You might say. Or you might throw out a question like “But wasn’t Ares also disliked by worshippers?” These questions are fair, but also ignore how polytheism in Ancient Greece worked. Ares had very few cults when compared to other gods, even though war was pretty prominent during this period of time in history. The desire to have victory in battle would lead to the occasional chained statue of Ares, seen as a way to pacify him and tie him to a specific people. Additionally, the personality of a god didn’t always deter people. They’d simply construct rituals to appease the gods, including rituals that involved the sacrifice of sacred animals.

DND though eschews some of these problems. Yes, there are Greek myths involving the gods visiting people, but again, here the existence of gods is unquestionable. Atheism is more so a declaration that the gods are just powerful immortal beings instead of being anything worthy of respect and praise, rather than the idea that any god doesn’t exist at all. Monotheism isn’t really a thing, though the exclusive worship of a god often is. But while I can understand how Zeus is praised in an Ancient Greek context, I struggle to see the point of the worship of a lot of figures in DND. The god will be like “I can’t stand you and you WILL die horrifically and be tortured for all eternity” and the cultists go “yayyyy” for some reason???? As other people have suggested, if a ‘good’ god offers far more benefits, why does anyone worship demons at all? There are plenty of horrible people who worship gods in real life that preach morals of acceptance and tolerance, so why wouldn’t the same happen in DND (and to a lesser extent, Pathfinder)?

The problem is alignment shit. Pathfinder avoids this - sort of - by providing the alignment of a god and then the alignments the god will accept from its worshippers. I still think alignment in general is stupid, but I get it. DND both cares about alignment and doesn’t. There is still this idea of innate evil that separates you from other gods in a pantheon when realistically, a lot of them wouldn’t care so much. You can be a bad person and still be an excellent mother. You can be a good person and find it impossible to worship a god of healing. I find alignment to be less compelling than actual personality considerations and the formation of contradictory philosophies regarding the gods.

Anyway, after saying all this, it might sound like I think Pathfinder is 100 percent perfect in terms of how it portrays faith because it does things like providing edicts and anathemas for gods, talks about how gods differ in depiction based on the region, and offers explanations for why certain ‘evil’ entities are worshipped (mainly due to nations having said faith as a state religion). I don’t actually think this because Paizo has its own weird hangups in terms of religion. Paizo is really weird about pregnancy. This review, thankfully, will not get into that though.

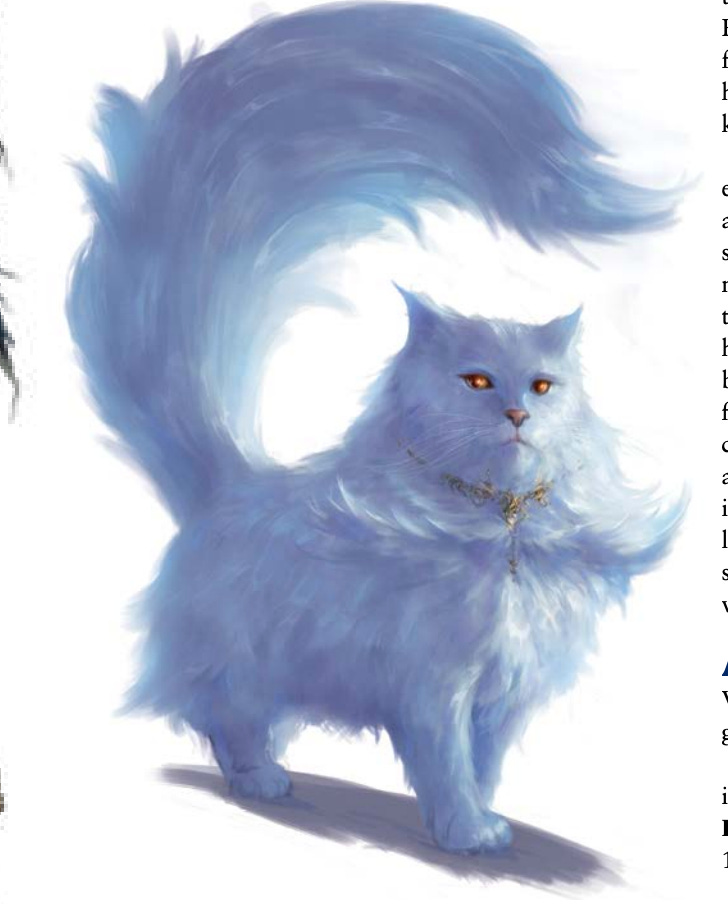

Instead, look at the kitty cat, everyone look at the kitty cat god-

It’s hard for me to pinpoint my favorite gods that are common in the Mwangi Expanse. I do have a fondness for Grandmother Spider. Clearly inspired by Anansi, her dynamic with mortals and immortals is very intriguing to me. I like any story that involves the rejection of slavery and retaliation against those who wield power against others, but I’m especially interested in her familial relationships, oddly enough. Like, sure, it’s one thing to know the anadi are associated with her and it’s another thing entirely that one of the most feared gods protects her without even lifting a claw. Achaekek being a deterrent while supposedly being indifferent to her existence is really compelling to me. Perhaps I’m reading too much into Asmodeus and Abadar’s disdain and yet lack of retaliation against her, but… Who knows?

I also like Kalekot. His area of influence is very varied, which is quite accurate for how most gods are. He’s a patron of abuse victims and those with facial disfigurements, but he’s also a patron for twins? He guards secrets and kills the guilty to save the innocent, but encourages the use of fear to protect the innocent? It’s all very interesting. I’d like to see a cleric or some other class who is associated with him in a darker campaign.

As a final note, I should say that Desna in the Mwangi Expanse is the best Desna and all other continents and nations simply do not understand that this goddess was made to be Black.

And until they understand this, they will never be a true follower of her /j

Some Geography

While I am a theology nerd and even, at times, an anthropology nerd, I would not consider myself to be a geography nerd. Once you start talking about the rain shadow effect or microclimates, you kinda lose me a bit. Again though, I think it is important to allow those nerds space to exist within a text like this. This section to me satisfies this need handily.

However, rereading it in order to talk to you guys about the more general geography instead of the more specific dives into actual settlements made my eyes glaze over. Yes, we get cool art like this.

And yes, I do think the book would be weaker as a whole if it excluded these sections. But at what cost? I’m bored!

Anyway, the main thing I wanted to say in relation to this part of the book is that it is very precisely designed with an intent in mind. That intent is not simply to be a sourcebook where you can read and learn about an area, but it is also meant to encourage you to imagine adventures of any length within the region. By providing so many detailed places that your party could conceivably explore or live in and sprinkling in threats and adventure hooks, it does this well. I’m simply not the target audience here. Besides, I think the next part is more interesting… despite my expression of disgust.

Some More Geography (Ugh)

Once you get through the bulk of the geography section, it doesn’t actually end! You just end up getting to the best part. The fun part. The settlements.

You get to Bloodcove!

If you have talked to me for any length of time, you know that I like fictional pirates. It’s funny because I never watched Pirates of the Caribbean or anything, mainly because I saw there were a bunch of white people in the photos for it and went ‘this isn’t the Caribbean!!!!’ and checked out as a young kid, but I like the idea of sailing the seas, fighting krakens, and tasting freedom. Perhaps it’s good I never got into the idea of pirates themselves historically due to their role in the slave trade, but this love extended to Bilgewater, a pirate-themed area in League with the best music, bar none. Every Bilgewater theme slaps. Also, there are cats with dagger tails.

Bloodcove scratches that same itch for me. I can imagine retooling Bloodcove for example to be like Bilgewater if I ever succumbed to the horrific temptation to play a Pathfinder game with a League reskin (perish the thought). But it’s honestly just super interesting on its own.

What makes Bloodcove - and honestly any of the settlement sections - interesting is the way it does its best to showcase what the daily life for a resident is like. Each one holds information on demographics and common religions, but that’s not all. Local food is explored, commerce is detailed (including when you can buy what and where), and how holidays deviate from elsewhere in a land shows up too. Here is where the departure from something like League occurs. I could tell you some very limited information about Bilgewater and its customs, but most of it would just be headcanon and extrapolation. I’d have far less to say about places like Ixtal or the Frejlord, just due to the lack of more mundane stories. Riot is more interested in its heroes and their larger-than-life adventures. Here, Paizo gives you a reason to feel as though this is a living, breathing world that continues on without players. It also presents NPCs you can use in games or simply dream up tales for.

And yes, there are recipes. I can’t vouch for or against their flavor though.

I think what ties it all together though is that none of these places, even the most majestic ones, are perfect. I don’t mean that in the sense of there being minor cultural flaws either. There are very real issues being explored in this work, such as how nations move forward after overthrowing regimes rife with slavery and how people atone for maltreatment against other peoples. At times, I found myself feeling uncomfortable with the narratives I was reading over. This isn’t a knock against the Mwangi Expanse’s Black authors, but more so just a recognition of how the diaspora addresses the topic of slavery differently in Afro fantasy. I can’t say the generational trauma I experience is fully rooted in a Haitian mindset, but considering the fact that the zonbi (yes, the zombie) was conceptualized in response to the idea that slavery persisting after death was the worst horror we could imagine… It's perhaps not surprising that I tend to avoid it when imagining nations populated by people with faces and hairstyles like mine. But my approach is not somehow the best one, and I think it’d be wrong to deny other Black people the space to put things like the fear of backsliding back into the days of slavery on the page.

I question how parties involving nonblack people approach the ethical questions and horrors in the book though. I don’t think the book is irresponsible or should only be sold to Black people or something, that’d be silly. I just wonder if the brief demands to respect the Mwangi Expanse, and by extension, people in the real world who were used as a cultural base actually work. I don’t really care what other people are doing though, at least not enough to justify digging into the matter further and potentially upsetting myself.

Instead, let’s switch to something I find more fun!

Monsters Sweep!

To end off the book, they give us a tidy little bestiary. Now, I love bestiaries. I’m sort of like Laios Touden if only because I feel that all fantasy settings need monsters or they’re basically pointless. This has been my belief since I was about 6 and I’ll never change my mind at this point.

I do however like bestiaries that are very clearly rooted in the vision for a fictional place much more. And this one delivers! Basically all of the monsters in this section have folklore that feel right out of stories I’d hear from my mom or grandpa. Look at this for example:

It’s soooo common for trickery to be such a central trait for our heroes, to the point where I’m surprised superhero stories haven’t incorporated that more often… Hm… Room for thought maybe? But, yeah, I think it’s just the fact that cleverness in the face of a stronger enemy is so valued that makes these made up stories stand out more. As far as I know, the above isn’t based on anything specifically, though anadi are Anansi references, as I keep mentioning. I think most of the other monsters are just remixes of existing animals in Africa but with cool powers. Which, you know what? I respect it. Hippos are already the best. Just slap fire on them and call it a day, like Pokémon or something.

That was kinda a weird way to end off, but I don’t really have much else to say, and this is already about 25 pages or so apparently. I guess the big question remains. Do I like this? Do I not?

Personally, I do like it a lot and I’m glad I used it as my entry point into reading modern Pathfinder. I keep comparing some of the earlier and later Lost Omens books to this, which is always a good sign. I would be interested in discussing it further with other Black people at some point, fans of Pathfinder or not. That’s mainly because I wonder how people judge the executions of specific plot points and mythological concepts who aren’t me. Maybe someday someone will see this and start a dialogue? That’d be neat.

Anyway, I’m not going to rate this or anything, that’s not how my reviews work. If I get off my ass, my next one will be a response to the Impossible Lands book, with the caveat that I have no actual ability to judge the quality of Jalmeray in relation to Desi identity and culture. Blasian grandparents and a brief stint in Dalit studies in college does not an OwnVoices review make, lawl

Thanks for reading though and the continual support. It makes me happy that people value my thoughts and opinions! I hope to get back to writing posts like this more regularly. I have an essay kicking around my brain about my problem with how other (not Caribbean though) Americans in the US discuss cultural exports from Jamaica and Haiti, how imperialism plays into this dialogue, and further thoughts on the problems with how people portray marginalized ATRs (marginalized and African traditional religion might be oxymoronic though while next to each other). We’ll see if it comes to fruition, I guess. Orevwa!